Who Killed the Yogurt Shop 4?

LISTEN NOW

Hello and welcome… to EPISODE 55, of WHO KILLED…?

PURCHASE WHO KILLED THESE GIRLS? BY BEVERLY LOWRY

I am your host Bill Huffman and on this week’s show, I will begin the arduous task of covering an infamous case out of Austin, Texas, the yogurt shop murders.

This case has been covered by the likes of 48 hours, Dateline, Inside Edition and a plethora of podcasts.

The reason I wanted to take a look at this case is I just finished Beverly Lowry’s book, Who Killed these girls? and it reinvigorated my interest in the case. I will do my best to do it justice and next week I may even have a special guest to discuss the case.

Let’s get this week’s episode rolling, Who Killed the Yogurt Shop 4?

December 6, 1991 started off like most days in Austin, Texas for Sarah and Jennifer Harbison.

They got ready for school, packed their book bags and headed off for the day.

It was an overcast day for the city, with temperatures maxing out around 72; a cool Texas Friday.

Austin, Texas in 1991 was just coming into its own as a nationally known place where creativity can thrive.

Not only is Austin, the capital of Texas, but it also holds the title of Live Music Capital of the World.

In 1994, the city created the Austin Film Festival and filmmakers and actors such as Mike Judge, Richard Linklater, and Matthew McConaughey call Austin home.

In 2002, Austin City Limits was founded and became one of the premier live events in the U-S drawing groups from all over the world to perform.

Sarah would be working that’s night shift so her plans were already set.

She would be working with Eliza Thomas, another classmate at Lanier high school.

For Sarah and Eliza their shift was going to be just like any other Friday night they worked together at the I Can’t Believe it’s Not Yogurt shop.

And the shift started exactly that way.

This was 1992 and the frozen yogurt fad was still in full swing; with lines at most times. The chain the girls worked for had hundreds of stores in multiple states.

Amy Ayers, a friend of the girls, and Jennifer Harbison, Sarah’s little sister came up to the shop to hang out. A normal routine for any teenager who has friends working by themselves. Their place of employment can become an ideal new hangout spot… We’ve all been there.

As the shift progressed, patrons came and went. It was a Friday night so the store was busy and the girls would be closing late.

Around 11:45 PM that same night a local police officer was on patrol when he took notice to smoke coming from the yogurt shop.

As the call went out to the fire department the blaze quickly became a two-alarm fire, requiring assistance from other departments to extinguish the fire.

In all, some fifty firefighters were needed to get the fire under control and prevent it from spreading to other stores.

What started off like any other day ended in horror for the four girls at the shop, the families, friends, the first responders and the community of Austin.

As the fire was being put out, nobody on the scene had any idea what they were about to find.

As the firemen moved into the building to finish extinguishing the hot spots, and any other little fires only to find something… I am sure they wish they could all forget.

In the back of the store, near the exit they found bodies piled on one another.

As the medical examiners were called in the grief the first responders were going through was clear. It was also obvious something horrible had occurred as the firefighters emerged dazed and confused.

One veteran police officer said he was stunned by the senseless killings of four teenage girls, all of whom were shot twice in the back of the head in a yogurt shop that was then set afire. “I’ve been on the force 10 years and lived in Austin 20 years and this is the worst I remember,” said Sgt. Scott Cary.

People had always believed the city to be safe, as cliche as that is, but now they were entirely gripped by fear.

On December 8th, 1991 A RELEASE from the Associated Press detailing the carnage these firefighters faced and the trauma these girls were forced to endure.

Police were at a loss but said robbery may have been a motive for the slayings and fire may have been used to cover the crime.

As the scene became overcome with rescuers, investigators and the media police said they have no suspects in the case.

As the fire was put out that, investigators were asking any customers who were in the I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt store around closing time Friday to come forward and talk to them.

The victims, all from Austin, were identified as Jennifer Harbison, 14; her sister, Sarah Harbison, 15; Eliza Thomas, 17; and Amy Ayres, 13. Officials said Jennifer Harbison and Eliza Thomas were store employees and that Amy Ayres was a friend. Autopsies were being conducted.

“Based on preliminary investigative work, robbery is being considered as a possible motive for the killings,” according to a statement from police.

“In our try for a why we like to hang our hat on that they were being robbed, I don’t know that for sure, that’s a possible out there, but I don’t know if we’re dealing with someone who’s high on drugs,” homicide detective John Jones told KLBJ Radio.

“I certainly hope so, because it doesn’t look like the act of a sane, rational individual,”he said.

Cary said police had not ruled out the possibility that the assailant, or assailants knew one or more of the victims.

The owners of I Can’t Believe It’s Not Yogurt issued the following statement shortly after the incident.

“We are shocked, saddened and outraged at this bizarre incident,” said Patty Reupke, the company’s director of marketing. “Our first thoughts are with the families. We don’t know yet any additional details. We are in contact with the police awaiting further information.”

Sgt. John Jones, who is in charge of the investigation said, “This is four girls that are now dead. For what reason? Surely they did not have that much money in there. The price of life seems to be getting cheaper and cheaper these days,” Jones said.

The Tarrant County medical examiner’s office said three bodies were burned beyond recognition, but there was little doubt about the identities. Dental records would eventually be used to confirm the identifications.

Austin police are sifting through available leads, hoping to come up with something that will produce an arrest.

“Unfortunately, we haven’t developed any real strong suspects. We are getting a lot of names, but nothing that appears like it’s going to break the case,” Lt. Andrew Waters said Sunday.

“We are still going on the theory that robbery was the motive. We don’t have any reason at this point to believe anything else,” Waters said. Police were asking any customers who were in the store around closing time Friday to come forward.

After reports of the fire, murder and robbery hit the wires, investigators in Las Cruces, New Mexico, had an uncanny feeling.

The police went on to say they were looking into the slayings at the Austin yogurt shop for any possible link to a 1990 bowling alley robbery that left four dead in Las Cruces.

Capt. Fred Rubio said a detective from the Las Cruces Police Department told Texas officials Monday about last year’s slayings in New Mexico.

Four girls, ranging in age from 13 to 17, were shot twice in the back of the head in Austin.

The case has similarities to the Feb. 10, 1990, Las Cruces shootings, which remain unsolved.

In the New Mexico slayings, two men robbed Las Cruces Bowl of $5,000 and shot all the witnesses in the back of the head. The robbers set a blaze to cover up the crime, but one of the victims was able to call for help.

Killed in that shooting were Paula Holguin, 6; her sister Valerie Teran, 2; Amy Houser, 13; and Steve Teran, 26, Valerie’s father and Paula’s stepfather.

Rubio said the Las Cruces Police Department has not gone over the cases in detail with Austin police.

“We haven’t gotten to the nuts and bolts of it yet. It was very unfortunate the way it was done. It’s just like ours,” said Rubio, chief investigator on the Las Cruces case.

Texas investigators said robbery appears to have been the motive in the yogurt shop slayings.

One difference in the cases the yogurt store victims’ hands were tied behind their backs. The victims in the bowling alley shootings were not tied up.

As the investigation went no where quickly fear began to grip a city that it once believed to be safe.

With hindsight being 20-20, I can see how the media embraced the idea of selling panic and fear. In the local Austin paper, the Statesman, the killings of four teenagers have created a new fear of crime.

“You wonder when you go out the door if you’ll ; come back,” says Barbara Fields of Austin. “I just don’t really feel safe.”

Statistically and comparatively speaking, Austin is a safe city. But when you have a killer or killers targeting young girls fear becomes the driving force behind decision making at the time.

Tell me if you don’t hear panic written within the context of this next passage?

“As senseless and random the yogurt shop slayings were, they have galvanized the community as few incidents or issues could,” cutting through our collective consciousness to a fragile sense of security barraged by a ceaseless stream of major crimes. A convenience store clerk is shot to death behind the counter. A cab driver stabbed to death behind the wheel. A woman is killed after leaving a dance hall. A man is stabbed to death as he arrives for work at a furniture store. A girl is sexually assaulted as she walks to elementary school. A college co-ed is beaten to death on the street. Police search for serial rapists in Hyde Park and Northwest Hills.

Statistically, Austin looks like a safe place to live, to work, to go to school, raise a family. But dozens of unrelated, serious crimes tend to build a sense of fear and foreboding.

The killings December 6th at I Can’t believe It’s Yogurt! West Anderson Lane brought those fears into the open.

Children, parents, employers, teachers became disillusioned, fearful and angry.”

It was a normal response but you can see how quickly the city becomes the reason for an increase or perceived increase in crime.

Days after the killings thousands of people mourned and hundreds helped bury Jennifer Harbison, Sarah Harbison, Eliza Thomas and Amy Ayers. But the concern and fear remains.

“A crime like this can create a panic,” said E. Mark Warr, a University of Texas criminologist.

“It suggests that the risk of being victimized has suddenly increased, or that we’ve underestimated the danger all along.” “It shakes you up,” said Tom Tinnell, who said he escaped California’s drugs and crime by moving his family to Austin, “You’re really not totally isolated from it.”

Although many people across the city say their fear of crime has increased, the crime rates in Austin were stable when comparing 1991 with 1990.

For the first nine months of 1991, there were 51 homicides, up two from the number of homicides in all of 1990.

People aren’t able to see the numbers for what they are… when fear comes with, well-publicized cases like the yogurt shop murders.

“It doesn’t make a difference what part of the city you live in. It’s going to happen no matter where you are,” said Tony Mendoza of North Austin.

Tina Hudson, who also lives in North Austin, said, “I hardly ever go out late at night. If I do, I try to be with somebody.

“It didn’t use to be that way,” she said.

Some professors believed violent crimes were on the rise and one of those was said by David M. Horton, professor of criminal justice at St. Edward’s University, “Yes, there is more crime out there. And it’s more violent.” Horton said he thinks violent crime “tends to create almost a national psyche, a national psychological mood of fear and suspicion. It’s not an indicator of general, overall health in a society.”

The killings in the yogurt shop brought back memories of the killings of three teens, dubbed “The Lake Waco murders,” in 1982.

Rude drivers race stoplight to stoplight, neighbors have become strangers, supermarkets have replaced corner stores. But crime here in Austin was really low when compared with other cities of similar size. New Orleans, with 496,938 people, has had more than 300 homicides at that point in 1991. Austin, population 465,622, has had 51. Fort Worth, with 447,719 people, has had more than 180 homicides in 1991.

The killings of the teenagers and the slayings of two men Friday were the latest in what the Statesman was dubbing a series of numbing acts of violence in Austin that have replaced trust with suspicion, wariness and fear.

They go on to say there are burglar bars on windows, alarms in cars, deadbolts on doors.

Private security firms were flooded with calls. Many women don’t walk alone, and parents keep a close watch on children.

The real estate market even changed due to the perceived increase in violence as apartment dwellers, especially women, began seeking safety in second-floor dwellings, which can put windows out of reach of assailants but unfortunately, where there is a will there is a way.

An apartment locator specialist said, “A lot of people 90 percent are women are requesting second floors, primarily in the past 2 months. They are scared to death.”

For the protection and a sense of security, some people turn to guns. One quote stated, “If you knew the true number of people arming themselves, I think it would come as a shock,” and this is Texas.

One gun shop said they received 15 to 20 calls a day are coming in from store owners and managers inquiring about the legality of carrying a gun or arming employees.

To be sure, not everybody feels vulnerable in Austin. Jennifer Schexnayder of Lakeway has lived in Washington, D.C., Houston and New Orleans. “This is the safest place I’ve lived,” she said.

But others are unimpressed with such relative safety. This next quote sums up the fear people faced in 1991 and how it impacted their perception of the city. “You want the truth? We want to get the hell out of this town,” said North Austin resident Rick Pope, who’s looking toward smaller towns to the north.

In an article by Pamela Ward of the American-Statesman staff stoked the fears of the city with her description of what children had to with in 1991.

Quote, “Violence has walked off the movie screen into real life. Kids don’t have to buy a ticket anymore to see savagery played out in Central Texas. Students this fall have dodged bullets while riding school buses home.

They’ve watched police shoot a 14-year-old at school when he rushed them with weapons. And last week, they lost four of their own to murder in a yogurt shop.

Violence is invading what seemed to be secure territory for children, and the impact is a range of emotions such as uncertainty, anger, anxiety.”

In Austin in 1991, parents were debating the safety of children working jobs where they were locking up the businesses. It was part cultural as the hispanic population wanted to instill a sense of responsibility with holding a job.

Five days after the killings I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt offered a $25,000 for information leading to the apprehension and indictment of the person or persons responsible for the December 6 murders of four teenage girls at I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt on 2949 West Anderson Lane. Anyone with information concerning this crime should contact the Homicide Unit of the Austin Police Department at 512-480-5025, in confidence.

Pamela Ward of the American-Statesman spoke with students who returned to classes and to the bitter realization that four of their friends won’t be coming back. In the article, she states, where Jennifer always sat, there was one empty desk the same for Sarah and Eliza and Amy.

Shock seemed to be the theme of the day. “Everybody’s still pretty much in shock,” said Shauna Kunkel, Lanier student council president. ”There’s a lot of denials; nobody wants to think this happened. Everybody is hurting.”

At Lanier high school lost three students, a dozen counselors huddled with students who asked for individual attention. PTA volunteers scurried about the hallways helping where they could.

Said vice principal Georgia Johnson: “A death from sickness or an accident, we could understand, but this, we can’t explain.” Nobody has an answer.

As one would expect after such a tragedy The Statesman said, “girls shed tears and hugged one another for comfort. Boys were more defiant in their grief. Some wore bandages on their fists, reminders of the rage they vented when they learned the news.”

Betty Phillips, coordinator of student intervention services for Austin Independent School District said, “There are strong feelings of revenge and violence”. “We have a lot of kids here who are very, very hurt and very upset and all their problems are coming to the forefront. Their feelings are what you would expect: There is just shock, horror, indignation,” said Amy Hettenhausen, a senior and with classmates.

The consensus was the girls were all vivacious, full of life, enthusiastic kids.

At Burnet Middle School where Amy Ayers was a student had counselors ready to talk with any students showing signs of being particularly troubled by the death of the popular eighth-grader.

In what can be a good example of dealing with death, the faculties from both schools met the day before classes resumed to support one another and to prepare for the students on Monday.

The goal was to create an environment of caring. There was no hysteria. Students seemed to find some comfort in being together.

A group of about 60 Lanier teenagers visited the yogurt shop at lunch that Monday as a way to relieve some of the pressure.

Parents were afraid for their own children, and children were frustrated and angry at the senselessness of the crime. The whole Northwest Austin community was gripped in fear. The idea that he was still out there somewhere and could be sitting across the street from the school limited the amount of comfort students could really feel.

Hettenhausen was one of at least a dozen student leaders who spoke to the press in the school’s main office. Each had volunteered, at the request of Lanier Principal Paul Turner, to express their feelings. The victims, all of them active in Future Farmers of America, were described as good students and leaders, popular.

The Statesman put together a timeline of this case and how it unfolded: Reading verbatim from the timeline:

- Dec. 6, 1991: Austin firefighters respond to a blaze at I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt! at 2949 W. Anderson Lane just before midnight. After the fire is extinguished, a search reveals the bodies of Jennifer Harbison, 17; her 15-year-old sister, Sarah; Eliza Thomas, 17; and Amy Ayers, 13.

- Dec. 8, 1991: Travis County Medical Examiner Robert Bayardo releases autopsy reports stating each of the four girls had been shot in the head. Police say they have no suspects.

- Dec. 9, 1991: Police discover evidence that they say leads them to believe more than one person was involved in the killings.

- Dec. 10, 1991: About 1,500 people attend the victims’ funeral Mass at St. Louis Catholic Church.

- Dec. 12, 1991: Travis County District Judge Jon Wisser seals autopsy reports on the victims at the request of the Travis County district attorney’s office.

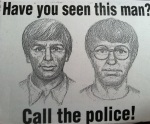

- Dec. 17, 1991: Police release possible psychological profiles of the killers.

- Dec. 31, 1991: The victims’ parents plead for additional help from the community during a news conference. Gov. Ann Richards releases a written statement asking for community assistance.

- Jan. 3, 1992: The Austin Police Department, along with local, county and federal authorities, form a task force to solve the case.

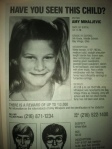

- Jan. 6, 1992 Police release additional information about the possible murderers. Twelve billboards display images of the slain teenagers.

- Feb. 26, 1992: Police arrest Laura Green on suspicion of stealing four tombstones. She is charged with theft by appropriation and questioned in the yogurt slayings. Her arrest came after intensive interrogation of a group of Austinites labeled by police as PIBs People in Black. Police later say Green is not a suspect in the slayings.

- Feb. 27, 1992: Local celebrities make a recording of We Will Not Forget, a song written by two local musicians and dedicated to the four slain girls. Proceeds from the song are donated to a fund established to help solve the yogurt case and reduce crime through education and counseling.

- March 16, 1992: Austin police release a sketch of a man seen parked outside the yogurt shop the night of the slayings. Police say the sketch resembles the sketch of a suspect In a November assault and abduction.

- March 25, 1992: The CBS news program 48 Hours focuses on the yogurt shop murders.

- June 3, 1992: The Austin business community adds $75,000 to the existing $25,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the people involved in the murders.

- June 5, 1992: About 1,200 people march from the Congress Avenue Bridge to the steps of the Capitol carrying white candles in memory of the slain girls.

- June 6, 1992: Six months after the murders, classmates of the slain girls graduate at Lanier High School, leaving seats for Jennifer Harbison and Eliza Thomas. Aug. 5, 1992: Police begin searching for three men indicted in a November abduction and sexual assault. The three men are Alberto Cortez, Carlos Saabedra and Ricardo Sanchez. The men are wanted for questioning in the yogurt shop murders.

- Aug. 7, 1992: The television program America’s Most Wanted airs a segment on the yogurt shop murders and shows photos of the three men listed in the kidnapping indictment, prompting about 60 tips.

- Oct 12, 1992: Austin sex crimes investigator Joy Mooney goes to Mexico City to give the Mexican attorney general a deposition about three men charged with abducting an Austin woman. One of the men in the abduction case fits the description of a man seen in a car outside the yogurt shop the night of the murders. Mooney is joined by two Austin homicide investigators, Sgt. Mike Huckabay and Lt. David Parkinson.

- Oct 16, 1992: The Austin investigators return from Mexico City. An officer says Mexican authorities were cooperative in the search for the three men wanted for questioning Alberto Cortez, 22; Ricardo Hernandez, 26; and Carlos Saavedra, 23.

- Oct. 22: Mexican federal authorities say that they have arrested two men wanted by Austin police and that one confessed to the murders of the four girls in the yogurt shop. Officials said Porfirio Villa Saavedra, 28, and Alberto Jimenez Cortez, 26, are being held. A third suspect is at large, officials said.

On October 23, 1992 the American-Statesman published an article titled “City breathes heavy sigh with arrests in slayings” by Tim Lott and Starita Smith.

The yogurt shop murders touched Austin at its very core. Residents of a city that always had seemed more like a town at least compared to Dallas and Houston began asking themselves troubling questions. What kind of cold-blooded person could kill four teenage girls? Is my neighborhood safe? Should I buy a gun? Can I walk to my car alone? Will it ever be the same? Though laced with hope, that raw emotion was evident again Thursday as word spread that Mexican authorities had made arrests in the Dec. 6, 1991, slayings of 17-year-old Jennifer Harbison; her 15-year-old sister, Sarah; 17-year-old Eliza Thomas; and 13-year-old Amy Ayers. Although they were arrests, not ‘ convictions, it was as if the city took a deep, hopeful breath. And then cried. “People were happy. People were crying,” said Lindsey Carey, a 14-year-old freshman at Lanier High School, where three of the girls attended school and the fourth would have been a freshman this year. “It was pretty emotional.” Students at Lanier learned the news over the public address system at the end of the school day. There were vivid accounts of when and how the news came. “Erik was watching TV and ran into my room saying, ‘They caught them!’ ‘They caught them!’ and we both started crying,” Kat Eich-horn recalled as she and Erik, her son, visited the site where the yogurt store once stood. The space is now occupied by a copying store. The Eichhorns made a trip to the site as soon as they heard the news. They placed four white candles one for each of the girls’ souls along a window ledge. “I wanted to light the candles to show my support of the girls,” Eichhorn said. “My daughter is 16. She’s been here many times. It could have been her. I’m glad someone was caught and I hope the families find peace.”

Other reaction was similar. “We are very happy that the police, after working so long and so hard, have been successful in making arrests,” said Jo Ann Kelly, director of human resources for Brice Foods Inc. and I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt! said, “I’m hopeful this will provide some relief for the victims’ families. Our thoughts and prayers are with them.”

For some students, the confession by one of the suspects, who said he shot all four girls, made their struggle to understand even more difficult. Samantha Tomaszewski, an 18-year-old who knew Sarah Harbison, burst into tears when she heard about it. “They’ve hurt hundreds of people,” she said. “They don’t know how many people they hurt doing this. Either they should be put in jail for 190 years or given the death penalty.” Paul Turner, the Lanier principal, said he hopes this is a turning point in the recovery of his school from the tragedy.

But Turner, like others, will not let his guard down unless there is a conviction. “I personally would rather there be some kind of closure to it than for us to be left hanging,” Turner said.

“I don’t know whether this will bring closure or not.” The family of Colleen Reed, the victim of another unsolved Austin crime, knows what it’s like to wait for resolution. Reed was abducted from a West Fifth Street carwash by two men just three weeks after the yogurt shop murders.

Last April, Belton resident Alva Hank Worley said he and a paroled killer, Kenneth Allen McDuff, kidnapped and sexually assaulted Reed.

Authorities arrested McDuff in Kansas City, Mo., in early May. McDuff hasn’t been charged in the Reed case. Reed has never been found.

“I’m ready for some closure,” said Reed’s sister, Lori Bible. “How much can you accept it when you don’t have a body to bury or a grave to go to? That’s the part that gets me.”

In a big blow to everyone involved, relief was short lived when the Mexican who was said to have confessed recanted his statement and said his confession came as he was tortured.

The investigation never quite went cold but there was a lull in the investigation until August 1999 when police assign six investigators and one sergeant and enlist the help of other agencies to pursue a new lead.

Just a few months later on Oct. 6, 1999, Austin police arrest Forrest Welborn, Maurice Pierce, Robert Burns Springsteen IV and Michael Scott on capital murder charges.

As quick as things move in Texas , it was only 2 months later on Dec. 9, 1999, when a judge rules that Pierce and Welborn, 16 and 15 at the time of the killings, may be tried as adults.

As the train steamrolled towards a conclusion on Dec. 14, 1999, a Travis County grand jury indicts Springsteen on four counts of capital murder. District Attorney Ronnie Earle announces he will seek the death penalty.

Four days later on Dec. 18, a grand jury indicts Pierce and Scott on four counts of capital murder. Prosecutors say they will seek the death penalty against Scott but cannot against Pierce because he was a juvenile at the time of the crime.

As the twists and turns continued it was in June of 2000 when a judge dismisses capital murder charges against Welborn after a second grand jury declines to indict him.

The train didn’t stop for Springsteen though because in April 2001 Jury selection begins in the capital murder trial of Springsteen. Prosecutors arrived in court armed with Springsteen’s confession but no physical evidence tying him to the crime scene.

Despite not having any physical evidence the jury reached a conclusion in June 2001 and sentenced Springsteen to death in the murder of Ayers.

About a year and a half later in September 2002, a jury convicts Scott of capital murder in the death of Ayers. He is sentenced to life in prison.

As quickly as he was charged on January 2003 charges against Pierce were dismissed, and he was released from jail.

As Springsteen sat on death row for nearly 5 years, in May 2006 the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals threw out Springsteen’s conviction, saying that Scott’s written confession was improperly used against Springsteen. The case is sent back to Travis County.

Then in June 2007, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals threw out Scott’s conviction, ruling that Springsteen’s confession was improperly used against Scott. Prosecutors said at the time they were prepared to re-try both defendants.

Then it all fell apart in April 2008 when a defense lawyer disclosed in a court document that previously undiscovered DNA that did not come from either Scott or Springsteen was taken from one of the victims.

A few months passed and on June 25th Springsteen and Scott were released from jail on their own recognizance after prosecutors tell state District Judge Mike Lynch that they’re not prepared to go to trial in July.

Prosecutors dismiss all charges against Scott and Springsteen.

Oct. 29, 2009 A judge dismissed murder charges against two men awaiting retrial in the 1991 killings of four teenagers at an Austin yogurt shop, after prosecutors admitted they were not ready to take the case to a jury.

One of the men, Robert Springsteen, was sent to death row in 2001 after he was convicted of capital murder in the killing of one of the girls.

The other man, Michael Scott, was convicted in the girl’s death and sentenced to life in prison.

Their convictions were overturned when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals said the men were unfairly denied the chance to cross-examine each other.

The men were released on bond in June after new DNA tests could not match them to the crime scene and revealed the presence of an unknown male.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0a8kKMMnCZs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LiVWDZ52mMc&list=PLG7WvHdg9adYsYaDzDw7PZFbl5J3W3zsF

Who Killed Amy Mihaljevic? a Slo Burn Podcast

Who Killed Amy Mihaljevic? a Slo Burn Podcast  Slo Burn Media

Slo Burn Media Support the show on Patreon!

Support the show on Patreon! Follow us on YouTube

Follow us on YouTube

Leave a comment